There are many uses for a dedicated GPU besides gaming. Potentially the most appealing, for homelab enthusiasts, is providing hardware accelerated transcoding of video files. Recent consumer graphics cards include dedicated hardware modules for both decoding and encoding the most common video compression formats. This allows the heavy lifting of video transcoding to be offloaded from the CPU, freeing up compute resources for other tasks and enabling faster, more efficient video encoding and decoding.

This is essentially the same functionality as Intel’s QuickSync hardware-accelerated video transcoding, but available on consumer and enterprise graphics cards as opposed to being part of the on-chip graphics package. Although I initially hoped to leverage QuickSync on my current processor, I have not been able to get pass-through of the integrated graphics working properly. I’ll cover those issues in another entry, but for now I want to talk about leveraging the dedicated video transcoding functionality of consumer-grade NVIDIA graphics cards.

NVENC On the Cheap

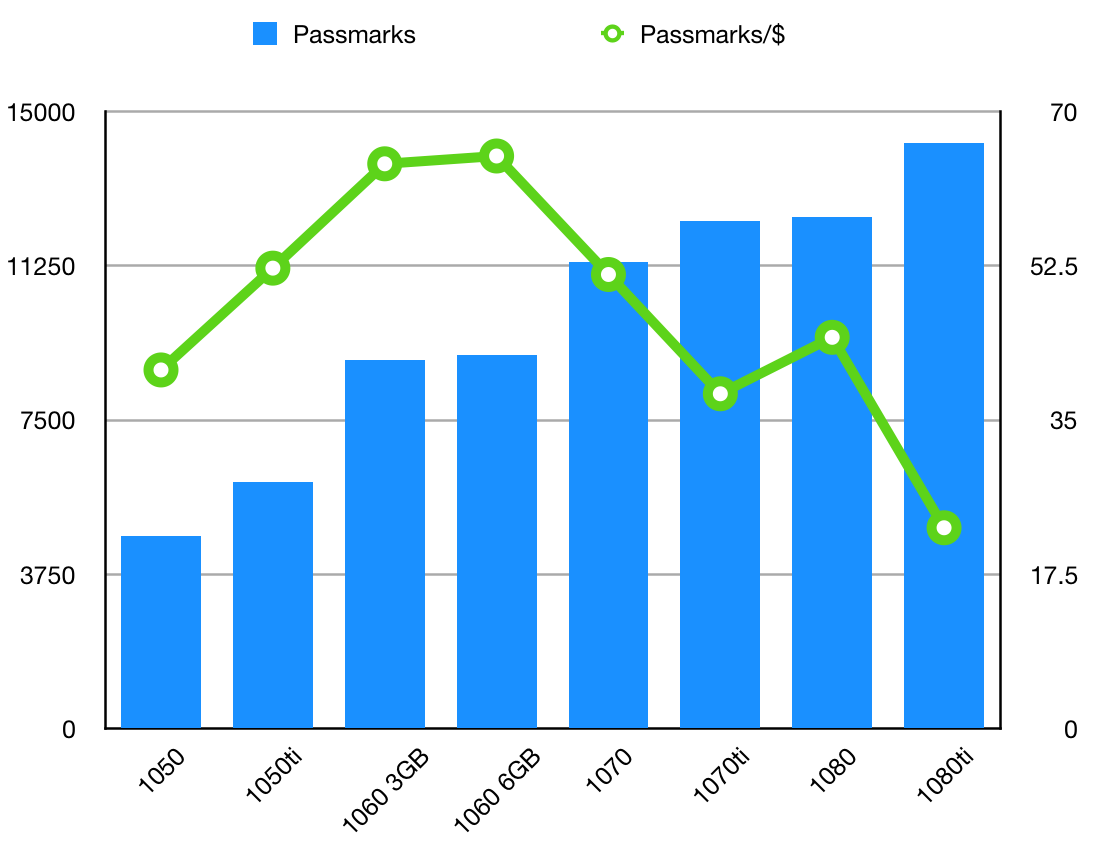

Today, the absolute best bang for your buck in the GPU market is a secondhand GTX 1060. With a Passmark score right around 9000, depending on the variant (8971 for the 3GB, 9095 for the 6GB), these GPUs have adequate performance for last-gen gaming at 1080p. And at a consistent local Craigslist price of around $140 USD, they represent an absolutely phenomenal 64–65 Passmarks per dollar. To illustrate my point, here’s the total Passmark score and Passmark/$ for typical local Craigslist prices for all 10-series GPUs:

As you can see, the 1060 variants lead the pack in terms of value, at more than double the performance per dollar of a 1080 TI. And while they may no longer be suitable for demanding gaming and rendering tasks due to their relatively low total performance, they’re still quite capable. Side note: while the GTX 1050 theoretically includes the hardware we care about, the overall graphics performance is much lower and the RAM is significantly less; the used market prices are not cheap enough to justify these shortcomings.

The GP106 chipset that first-gen GTX 1060 cards are based on is the same as in the Quadro P2000. Like almost all Pascal architecture GPUs, it features dedicated hardware for video encoding and decoding. Looking at the official video codec support matrix, we can also see that this chipset is recent enough to support modern codecs, including up to H.265 4K YUV 4:4:4 encoding and up to H.265 12-bit YUV 4:2:0 decoding. H.265 4:4:4 is still relatively uncommon, and hardware decoding for it isn’t supported on any Pascal architecture card, so we’ll accept that as a reasonable upper limit.

Quadro vs. GTX

So what’s the difference between a Quadro P2000 and a GTX 1060 when it comes to video transcoding? On the hardware side, not much that I’ve been able to find. The memory size and bus width differ, but the decode/encode module appears to be the same. Of course, NVIDIA imposes a number of artificial software-based limitations on their GTX cards designed to force enterprise customers to pay the premium for the Quadro brand. For video encoding, this manifests as an artificial restriction on the number of simultaneous transcoding sessions supported by the driver. Where Quadro cards (from the P2000 and up) are “Unrestricted”, all GTX cards are capped at 2 sessions. What does the potential performance look like if we ignore this restriction?

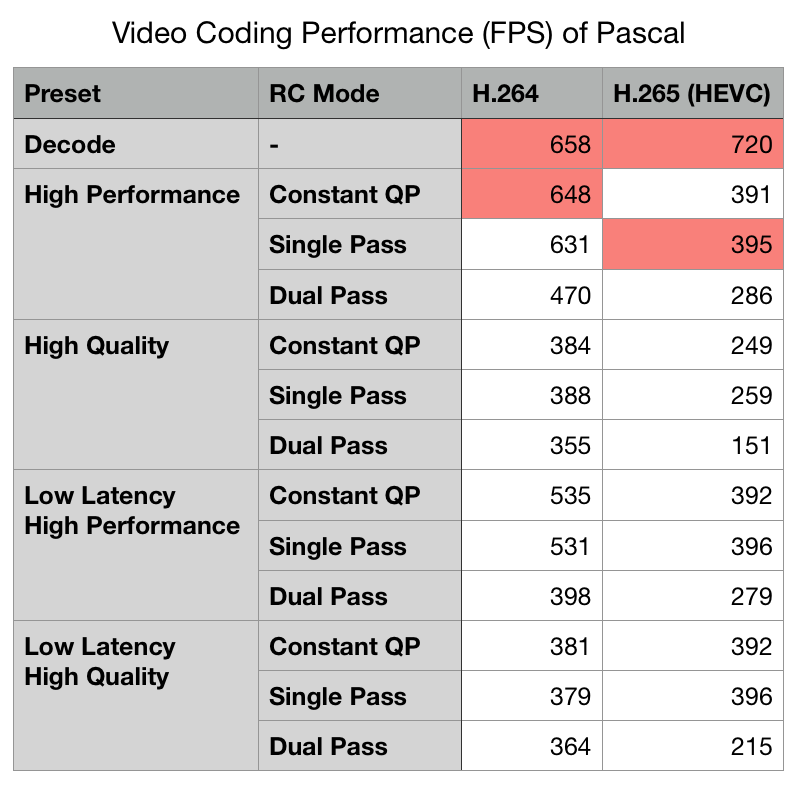

According to the latest revision of NVIDIA’s technical notes for NVENC and NVDEC, the maximum performance for encoding H.264 is 648 FPS, while decoding is 658 FPS. This is a per-module performance figure, so it doesn’t depend on the GPU chipset generally but only on the number of modules included in a specific GPU’s configuration. The P2000 and GTX 1060 both feature single NVENC and NVDEC modules. Here’s a look at Pascal video coding performance by quality option:

Doing a little simple math (Encoding FPS ÷ 30 FPS per stream) we can estimate the performance for multiple stream encoding. A single NVENC module should be capable of encoding 21 simultaneous streams in High Performance mode and 11 in High Quality Two-Pass mode. NVDEC performance is similar, at 21 streams regardless of their encoding level. A P2000 or GTX 1060 should be able to perform the theoretical maximum 21 simultaneous 1080p30 transcodes on its single NVENC module, minus some potential overhead for task switching and performance degradation from memory restriction. Of course, this is all hypothetical, but YouTuber Alex over at Sloth Tech TV reports that he was able to achieve 18 streams on a P2000. That seems fairly realistic, and is in the ballpark for previously-published numbers for Pascal NVENC modules (575 FPS, according to a previous version of the technical notes), as well as being approximately what would be expected when accounting for the lower boost clock speed of the P2000 compared to the GTX 1060.

Hardware Transcoding, Un-Capped

What does this look like in the real world? Thanks to some clever reverse-engineering of the NVIDIA drivers, it is now possible to un-cap consumer GTX cards for unrestricted video transcoding. This is the same basic technique used by DifferentSLIAuto, the utility for enabling SLI on unsupported hardware configurations: we simply patch some new data into the right memory address in the driver blob. Fortunately, others have already gone to the trouble of verifying this modification and have even put together a simple shell script that will safely do it for you.

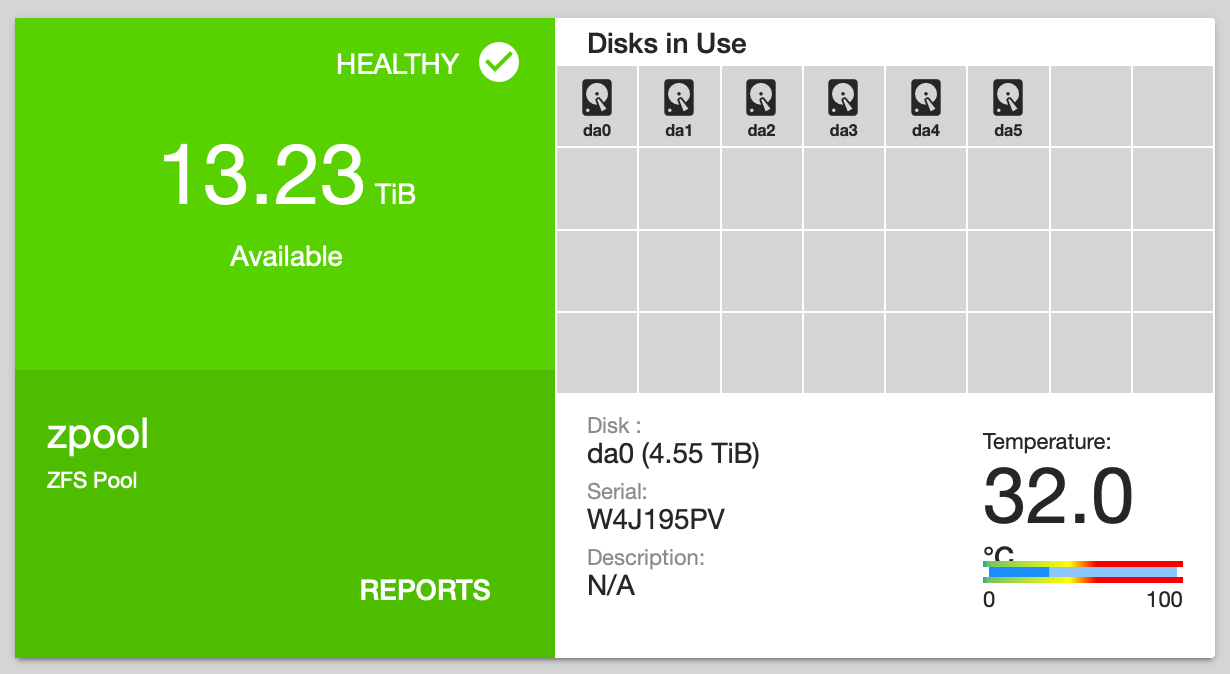

Unfortunately, this driver requirement means that it’s not possible to do this under FreeNAS, so I’ve spooled up a fresh Ubuntu Server 18.04 VM for testing purposes. First things first, we’ve enabled PCI Passthrough on the GPU in the Host’s hardware configuration. Then we simply add the card (and its associated audio device, even though we won’t be using it) to the VM as a regular PCI device, making sure to reserve all guest memory:

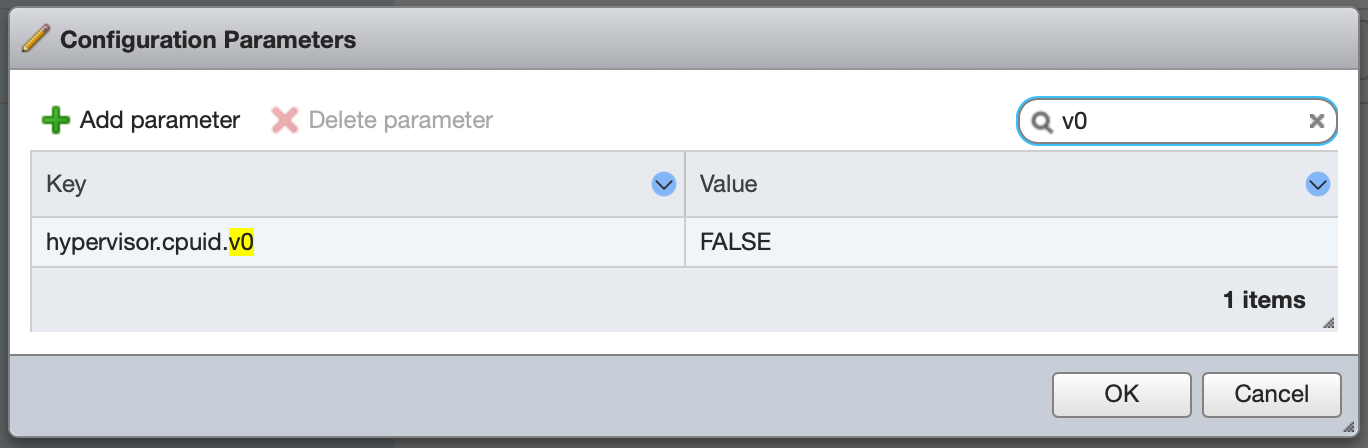

Then we hide the hypervisor from the guest OS so the NVIDIA drivers will load and not simply refuse to work. Add hypervisor.cpuid.v0 = FALSE under the guest’s Advanced Configuration:

Finally, although it was necessary for functionality under Windows 10, I have not found any trouble with Message Signaled Interrupts under Ubuntu 18.04. If the GPU is flaky, it may be necessary to configure pciPassthroughX.MSIEnabled = FALSE for each device; I’ll update this entry if extended testing surfaces any stability problems.

Now we can boot up the VM and install the NVIDIA drivers. The caveat here is that you need a version of the driver which is supported by the patcher. A list is maintained in the README; for Ubuntu 18.04 I was able to use the community PPA to install a version 415 driver, which was using a compatible point release supported by the patcher:

$ sudo add-apt-repository ppa:graphics-drivers/ppa

$ sudo apt update

$ sudo apt install nvidia-driver-415

Once this is done, reboot the system and check functionality with nvidia-smi. You should see your card(s) listed alongside some performance stats:

$ nvidia-smi

Wed Apr 3 04:07:20 2019

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| NVIDIA-SMI 415.27 Driver Version: 415.27 CUDA Version: 10.0 |

|-------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

| GPU Name Persistence-M| Bus-Id Disp.A | Volatile Uncorr. ECC |

| Fan Temp Perf Pwr:Usage/Cap| Memory-Usage | GPU-Util Compute M. |

|===============================+======================+======================|

| 0 GeForce GTX 106... Off | 00000000:0B:00.0 Off | N/A |

| 18% 55C P0 29W / 120W | 10MiB / 3019MiB | 0% Default |

+-------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| Processes: GPU Memory |

| GPU PID Type Process name Usage |

|=============================================================================|

| No running processes found |

+-----------------------------------------------------------------------------+

From here, instructions proceed as documented in the patch README. Clone the repo then simply run bash ./patch.sh. The script will automatically validate the driver version, locate the blob, and apply the patch bytes. Reboot to complete the process.

Full Transcoding With Plex

In order to test out our new hardware configuration in a common real-world scenario, I’ve selected the personal cloud streaming software Plex. It runs on pretty much anything, and will allow us to verify both encoding and decoding functionality without having to manually invoke something like ffmpeg a bunch of times and then do napkin math to figure out what that means for other workloads. This will allow me to test multiple simultaneous real-time transcoding sessions in a realistic environment.

There are a couple caveats to hardware transcoding with Plex. The first, of course, is that you need a Plex Pass subscription to enable the currently-beta Hardware Accelerated Transcoding feature. The second is that you actually need to be running one of the latest beta releases if you want to enable hardware accelerated decoding on NVIDIA chips. Although QuickSync/VAAPI hardware decoding has been available for a while, NVENC support too, NVDEC support is a recent addition.

According to Plex Forums user AnonymousRetard, the main change in Plex appears to have been updating the version of ffmpeg they use for transcoding to a more current release that supports NVDEC. However, this change is so recent that it’s not even unofficially supported in the beta releases, so some slight modification is needed to inject a flag to the encoder to enable support.

User revr3nd on the Plex Forums has put together a handy guide and convenient little script for this part of the process. Essentially all you need to do is get a copy of Plex version 1.15.1.791 or later and then patch the Plex Transcoder with a shim to conditionally inject the NVDEC argument when invoked on supported codecs. Find it on GitHub; I did have to submit a PR with a couple fixes, though, so your mileage may vary. Since NVDEC only works on certain codecs, it’s important that Plex doesn’t attempt to use it when it won’t work. The codecs supported vary by architecture, chipset, and specific card version. Although Pascal generally supports MPEG-1, MPEG-2, VC-1, H.264, and H.265 4:2:0, support for VP8 and VP9 10- and 12-bit is only found on some cards.

Confirm which codecs are supported by your GPU (check the NVDEC support matrix) and invoke the script accordingly. In our case, running a GTX 1060 (GP106) under Ubuntu, the command is:

./plex-nvdec-patch.sh -p /usr/lib/plexmediaserver -c h264 -c hevc -c mpeg2video -c vc1 -c vp9

Note: you will need to re-run this command every time Plex is updated, until NVDEC is officially supported, since upgrades will overwrite the shim.

Performance

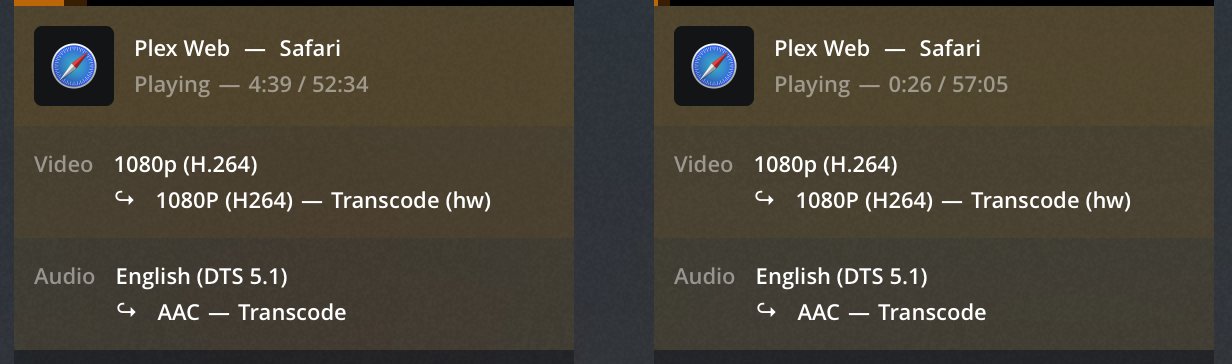

Finally, the moment of truth, that magic “(hw)” on the Dashboard:

To confirm that hardware accelerated decoding is active, check the “dec” output column of nvidia-smi dmon -s u:

# nvidia-smi dmon -s u

# gpu sm mem enc dec

# Idx % % % %

0 3 0 0 0

0 5 2 10 16

0 27 9 48 38

0 34 10 62 43

0 36 11 66 47

0 37 12 67 48

0 33 10 59 43

0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 1 0

0 0 0 0 0

Utilization will spike when you initiate a new stream, as Plex transcodes a buffer, and will then settle out to low values as the transcode keeps up with playback.

Over a short four minute test interval running six transcodes from H.264 1080p ~17Mbps to the 10Mbps preset, I measured 24.5% encode utilization and 21.1% decode utilization average from nvidia-smi. CPU utilization, only for container and audio codec transcoding, was minimal, at a little under 10% per stream (note that percentage is per-core: total system capacity is 400% utilization). However, reported CPU usage from the ESXi host was rather high, with total combined CPU use from the FreeNAS and Plex VMs averaging around 85% of total capacity during this stress test. This was largely due to file transfer overhead of SMB, which should be improved by switching to NFS or iSCSI.

As much as I would like to further test this setup, I don’t have enough playback devices at hand. I intend a more thorough performance report when I am able to borrow additional playback devices.

That’s it for now.