I thought it would be fitting for my first post on this blog to be about something I wrote many years ago, but which still lives to this day.

In grad school (University of Washington), I worked in a lab that acquired a DEC MicroVAX II. This machine was configured with either Ultrix (DEC’s version of Unix), or BSD Unix, and ran the X Window System (X10 R3 or R4). I used this machine quite a bit during my M.S. research. So I ended up with a degree in Computer Science, and some practical and then-quite-relevant skills in C, the X Window System, Unix, workstations, and computer graphics. As an historical note, the workstation’s main purpose in life was to act as a front end for an Adage/Ikonas frame buffer, but to get that to work, Jamie Painter and I had to rewrite part of the device driver for it, to accommodate the Q22-bus peculiarities. I made the mistake of putting that experience on my resume, and for years I was hounded by recruiters seeking people who actually liked working on device drivers, of which I was not one.

My first job out of grad school was with Digital Equipment Corporation, at their Workstation Systems Engineering (WSE) group in Palo Alto, California. Readers may, with some justification, associate DEC with VMS and “big iron”. But we were part of a “rogue” division, which focused on creating both the hardware and software for Unix-based graphics workstations. My grad school background was a pretty good fit there, as one of WSE’s responsibilities was the X Window System implementation for Ultrix, which included X3d, the 3D extension to X (later transmogrified into PEX, but that’s another story). This coincided with the time that X11 was first released.

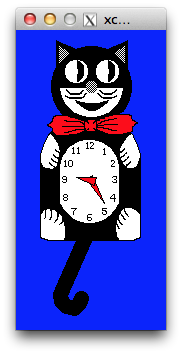

One of the earliest X10 applications was xclock, and it looked like one of these, depending on whether you asked for an analog or digital version:

(Well, not exactly like this…the window manager would probably not have put an OS X title bar on it, in the mid-nineteen-eighties. By the way, OS X makes for a pretty dandy X-based workstation these days.)

At home, I had one of those plastic Kit-Cat clocks, and thought it would be fun to make a variation of xclock that paid homage to this American icon; this was some time in 1989 or so. Somewhere I got my hands on the sources for a version that had an alarm and chime feature. I’m not sure if this ever was part of any X10 or X11 release, and searching around on the web turns up no trace of the source code; I think it may have been written by Ed Moy, but that’s just a vague memory. A lot of variants were floating around in those days, thankfully all under the MIT license. And I was working at DEC, which was significantly involved with the X Window System’s development, so it could have come through some non-public channel…

The released version of X11’s xclock had been reimplemented as a Widget, but I wanted to keep the alarm/chime feature. At this point, the details are quite fuzzy…an old readme file suggests I myself ported it from X10 to X11, but I’m not entirely sure (I sent a request out on comp.windows.x, but I just don’t recall if that was that path by which I’d acquired the sources). In any case, in its first X11 iteration, it used the Athena Widgets; I subsequently ported it to use Motif, which was all the rage back then (my only regretful decision here). With MIT-licensed sources in hand, I began my development.

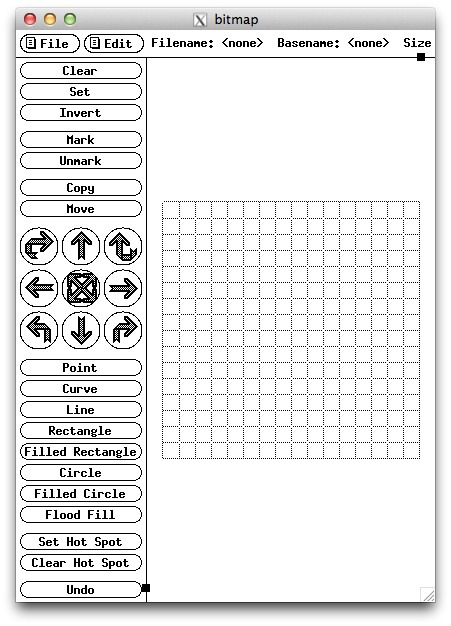

I chatted up this project with some colleagues, and Deanna Hohn offered her services to create the graphics for the “cat mode”. This being the late nineteen-eighties, and the project being an X application, the only tool worth considering was the venerable bitmap application:

Yep, another application from the X10 days, and little changed since then. With this high-tech artist-centric tool in hand, Deanna crafted the xbm files for the Kit-Cat-like graphics.

If you’ve seen a real Kit-Cat clock, you know that the eyes rotate back and forth, in conjunction with the tail swinging. So, we knew we’d want this as well in our xclock variant. The X Window System wasn’t really intended to be a drawing/rendering API, and so the available functionality was limited to just a handful of very basic functions with minimal stylistic controls (drawing a polyline with some specified type of joins, or creating a filled polygon).

The catclock’s eyes’ appearance and motion needed to capture the charm of the Kit-Cat’s spherical eyes, so the challenge was to try to replicate the depth and motion with a very simple 2D “drawing” API. As a geometry/graphics nerd with altogether too much spare time on my hands, I realized that the best approach would be to simulate the motion of the spherical eyes in 3D, and then to project the 3D points onto a plane; the resulting points could then be passed to an X drawing function. So the code creates a number of bitmaps on the fly, each with the eyes rotated at increasing time (and therefor angle) increments. The first iteration of the code just had the eyes moving back and forth at a constant velocity, and similarly with the tail. But, while this looks kinda OK on the real clock, in the program it just looked peculiarly wrong. A little application of a pendulum equation fixed that right up.

The tail on the Kit-Cat clock is a simple affair — it just dangles down with a slight wave to it, and tapering a bit at the end. In my implementation, the tail bitmaps are drawn with an umbrella-handle-shaped polyline, with a round cap on the end. I don’t really recall, but I must have thought this would work out better than trying to be faithful to the real clock’s tail.

The outcome of all this brilliant artistic and mathematical creativity was the “cat mode” for xclock:

Amongst programmers, this sort of silliness counts as high humor, and so it went viral (relatively speaking), and I sent out many copies (tarred sources, naturally) for quite a few years after that. Before the demise of DEC, it was even ported to run under VMS.

So what’s the point of all of this?

The original X10 xclock dates from 1984 or 1985. I ported/hacked this X11/Motif version around 1989 or 1990. Since then, the source code has been changed very little, primarily in response to more strict C compilers. Today, the source compiles and runs on OS X, Linux, and Cygwin, with the only changes necessary being header and library paths in the Makefile for OS X. Yep, 30 years of legacy in an industry and science noted for its fast-paced evolution.

Depending on how you feel about X, or C for that matter, this longevity is either a tribute to good, solid design, or a sterling example of how poor, primitive solutions can stay around well past their proper lifetimes. I’m in the former camp, for what it’s worth. But either way, it’s a kinda cool that a toy I made so many years ago still works.

Source code is available on github. I’ve made no attempts to modernize the code beyond what’s been needed for more strict compilers, and so it’s fairly “old school” in every respect (remember, some of it is around three decades old at this point, and the remainder is not much younger).